When I first started learning about French charcuterie and forcemeat, I got confused a lot and I didn’t know what made pâté and rillettes different (or even what they really were). But now that I know more, I wanted to share this information with you too.

What’s the difference between pâté and rillettes?

Pâté is a meat and fat paste cooked until firm and sliceable, also called pâté en terrine and terrine. In North America, pâté often refers to a liver spread, also called liver mousse, chopped liver and chicken liver pâté. Rillettes are a cooked and shredded meat spread—generally pork and another meat—with a chunky texture. They’re also called potted meat.

Now that you know the main difference between pâté and rillettes, you still may want to know more about them, where they fit into the realm of charcuterie and forcemeat and if you can serve them the same way. If yes, keep reading! I’ll start with more detailed definitions of pâté and rillettes.

What is pâté and (pâté en terrine)?

To distil pâté down to its essence, it’s simply meat and fat ground into a paste and cooked. If this pâté is cooked in a terrine—and it often is—we call it pâté en terrine or just pâté for short. If this pâté is cooked in pastry, we call it pâté en croûte, even in English as we’ve adopted these French words as our own (which is common for cooking terms).

This definition distillation doesn’t do pâté justice. Meat paste sounds gross! Yet the final product, sliceable pâtés which often have interior garnishes such as other chunks of meat, pistachios, dried fruit, etc. are quite delectable.

Pâtés are generally made of pork or pork and other meats.

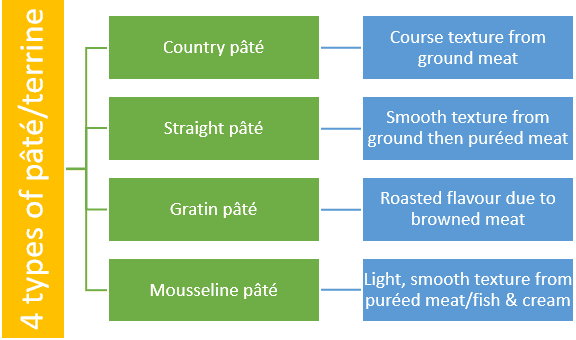

There are four classifications of pâtés: straight pâtés, country pâtés, gratin pâtés and mousseline pâtés.

Diagram: Pâté classification

In their book, Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking & Curing, Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn say mousseline forcemeats “are the easiest forcemeat to make at home because they are so stable, the ingredients are commonly available, and you just blend the ingredients in a food processor.”

What is spreadable liver pâté?

In North America, when we’re eating a spreadable liver concoction, we call it pâté, liver pâté, chicken liver pâté, chicken liver mousse or chopped liver, depending on the recipe. A chicken liver pâté can be cooked like a pâté en terrine, which is in the oven in a terrine placed in a water bath.

However, most times you see a recipe for a chicken liver pâté (or duck, cow, pork liver, etc.), it’s first cooked on the stovetop and then blended up into the spread.

In many cases, it would be more accurate to stop calling it chicken liver pâté and call it chicken liver mousse instead. In their book, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie, Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman say, “Mousse is a purée of cooked food, often enriched with cream, with a soft, smooth texture, as in chicken liver mousse.”

(Mousseline, on the other hand, is puréed when the ingredients are raw.)

So basically, if you grind then cook, it’s a pâté or terrine. If you cook, then blend (and often pass through a strainer), it’s a mousse or what we think of in North America as chicken liver pâté.

Chopped liver, a liver dish common in Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine that typically includes boiled eggs, can be smooth like chicken liver mousse or left quite chunky. If you’ve got a hankering for chopped liver, check out Tori Avey’s Chopped Liver recipe on her website. Plus, in this recipe, you get to discover (like I did) what gribenes are.

What are rillettes?

Rillettes are a cooked meat and fat spread that typically ends up rather chunky. In her 1981 book, French Regional Cooking, Anne Willan says, “Half pâté, half purée, rillettes are usually made from fat pork. The proportions of fat to lean vary from half to almost equal. The meat is baked very slowly in a closed pot until it falls apart, in much the same manner as English potted meat. It is then shredded with a fork, mixed back into the melted fat and left to set.”

For preservation, the top of the rillettes jar is also covered with a layer of fat. [For more information on how long rillettes last in the fridge, check out my article, How Long Do Rillettes Last? A Long Time So Eat Up!]

Rillettes are super easy to make, all you do is throw everything in a pot and follow Anne’s instructions above. Plus, unlike with chicken liver pâté, there’s no gross part (if you consider washing, soaking and trimming livers a little gross, that is).

Like pâté en terrine, rillettes use pork as a main meat and can be mixed with many other meats including rabbit, duck, goose and game.

Rillettes are much loved in France and some even have specialty status. According to The Guardian article, What’s better than a rich French paté?, “In 2013, producers of Rillettes de Tours secured EU protected geographical indication status for their product. Producers further north have been trying to obtain the same protection for Rillettes du Mans for 20 years.”

This means that if you’re eating rillettes de Tours in France, you’re guaranteed authenticity.

Is pâté classified as charcuterie or forcemeat?

Pâté is classified as forcemeat and it can be classified as charcuterie if it gets another preservation treatment such as smoking or adding a layer of fat over top to keep the air out.

According to Australia’s Taste website article, Complete how to guide to terrines, “Terrines can last, sealed from the air under a thick layer of rendered fat, for weeks, if not months. This recipe will keep, wrapped tightly in foil, for up to two weeks in the refrigerator.”

That’s pretty good for preservation.

To explain this answer further, it’s probably best to define both charcuterie and forcemeat as there’s some overlap and possibly confusion.

What is charcuterie?

In the book, Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, The Culinary Institute of America (CIA) defines charcuterie as, “The preparation of pork and other meat items, such as hams, terrines, sausages, pâtés, and other forcemeats that are usually preserved in some manner, such as smoking, brining, and curing.”

However, I think Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman provide a more helpful definition in their book, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie. They say, “Charcuterie is a broad term for all those preparations that were created to extend and preserve meat—whether taking raw scraps of meat and offal and creating a pâté en terrine, grinding and stuffing sausage, or curing a ham.”

You can also think of charcuterie as a love letter to the pig. As Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn say in another book, Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking & Curing, “Of all the world’s foods that can be preserved to great effect, the pig has proved to be the most versatile. It is the only animal that has generated its own culinary specialty: charcuterie.”

Or, as Homer Simpson famously said, “A wonderful, magical animal.”

The two main points I’ve learned about charcuterie are:

- In its essence, it’s about preserving meat.

- Pigs are wonderful.

What is forcemeat?

Forcemeat simply means ground meat. But to get a little more specific, I’ll go back to the Garde Manger for a definition. The CIA defines forcemeat as “A mixture of chopped or ground meat or seafood and other ingredients used for pâté, sausages, and other preparations.”

Other preparations can include quenelles, stuffed ravioli, galantines and ballotines, etc.

Are rillettes classified as charcuterie or forcemeat?

Rillettes are classified as charcuterie because they are preserved meat. They’re not forcemeat because forcemeat is ground meat and the grinding happens when the meat is raw. With rillettes, the meat is shredded after cooking.

[As I joke on my About page, perhaps I should’ve called this website Charcuterie Academy instead of Forcemeat Academy but who wants to say all those syllables?]

Are rillettes and pâté served the same way?

Another source of confusion can stem from the fact that although rillettes and pâté are different, you can basically serve and eat them the same way. This applies whether you’re dealing with the sliceable pâté en terrine or the spreadable chicken liver mousse pâté.

Pâté and rillettes are often served with bread and other elements of a charcuterie board such as fig jam, pickled vegetables, cheese and olives. Pâté and rillettes can also be used in sandwiches, on salads, as part of a meat-enhanced ploughman’s lunch or straight from the container into your mouth (only when you’re alone).

[For more ideas on chowing down on rillettes in style, check out my article called, How Do You Eat Rillettes? Sandwiches, Nibbles and More! This article also contains recipes for keto and carnivore “bread” in case traditional bread doesn’t agree with your digestive tract.]

Conclusion

Well, there you have it. Even though pâtés and rillettes, both made of meat and fat, are different, you might love them both just the same. May all your pâté and rillettes be a delicious and glorious experience!