Pâté and forcemeat are culinary terms, one common and one obscure, yet very much intertwined. But what exactly are they, what makes them different or are they actually the same thing? If you’re dying to know the answer to these questions, you’re in the right place! I hope you enjoy this helpful article about pâté and forcemeat.

So…what’s the difference between pâté and forcemeat?

Pâté is a meat and fat mixture cooked until firm and sliceable, also called pâté en terrine and terrine. Pâté can also describe liver spreads such as liver mousse, chopped liver and chicken liver pâté. Forcemeat is a mix of ground meat and fat (or seafood) used for charcuterie dishes such as pâtés, sausages, galantines, quenelles, etc. Forcemeat comes from the French verb farcir which means to stuff. Pâté is forcemeat but not all forcemeat is pâté.

Now you know the basic differences, let’s take a closer look at what forcemeat and (the sliceable and spreadable kinds of) pâté are, the various ways you can use forcemeat and the differences between pâté and forcemeat. As a bonus, I’ll link to my favourite liver pâté recipe that even works well with pork liver. But first, let’s get one definition out of the way…

What is charcuterie?

I mentioned pâté and forcemeat are found in charcuterie. But what is charcuterie other than a French word associated with a cutting board full of salami, cheese, cornichons and Dijon mustard?

We’ll look to the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) for guidance. In their epic book, Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, the CIA defines charcuterie as, “The preparation of pork and other meat items, such as hams, terrines, sausages, pâtés, and other forcemeats that are usually preserved in some manner, such as smoking, brining, and curing.”

What is pâté?

Pâté is meat and fat ground and mixed into a paste and cooked. It generally contains other ingredients for flavour and texture (more on the ingredients in a moment).

Pâtés are often cooked in a mold called a terrine. In these scenarios, we call the final product pâté en terrine or just pâté or terrine for short. If the pâté is cooked in pastry, it’s called pâté en croûte, even in English. Of course, you can find recipes for “pâté in a pastry crust” but the French term is widely used in cheffy circles, especially charcuterie circles. There are many French terms adopted into English culinary vocabulary. (Pâté literally means paste so you can see why we like the French version better.)

Pâtés are generally made of pork or pork and other meats including game. For texture and design, they’re often made with structured inlays (large pieces of meat) or interior garnishes which are smaller chunks of meat, pistachios, dried fruit, etc.

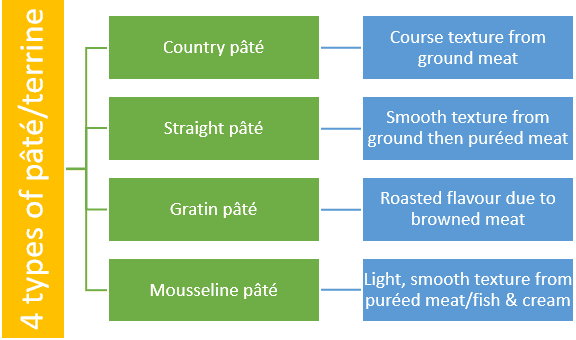

Pâtés are classified into four categories: straight pâtés, country pâtés, gratin pâtés and mousseline pâtés.

Diagram: Pâté classification

All of these pâtés are firm and sliceable; they may contain liver (except mousseline pâté), but then again, they may not.

Common pâté ingredients include:

- Pork and other meats such as duck, rabbit and game.

- Liver.

- Spices and/or aromatics.

- Port, brandy or wine.

- Stock.

- Heavy cream.

- Eggs.

- Butter.

- Bacon, caul or fatback.

- Lard, duck fat or butter to create a fat seal.

- Breadcrumbs and milk (for a panade).

What is spreadable liver pâté?

In North America and the United Kingdom, when we’re eating a spreadable liver paste (see what I mean about that word?), we call it by many names. It could be pâté, liver pâté, chicken liver pâté, chicken liver mousse, chopped liver, etc. We could also get into calling it pork liver pâté or duck liver pâté, basing the whole name on the kind of liver used.

Unlike with most of the pâté classifications listed above, liver is not optional in this type of pâté. It’s generally the only meat in the recipe and is accompanied by a generous amount of butter and/or heavy cream. (The less you like the taste of liver, the more butter is required for you to like liver pâté.)

The two main differences between chicken liver pâté and pâté en terrine are:

- Texture – One spreads while the other one is sliced.

- Cooking method – With the spreadable chicken liver pâté, you cook the ingredients on the stove top then blend them up together. With pâté en terrine, you mix the ingredients, add them to your terrine and cook it in oven in a bain marie (water bath).

Chopped liver is a common in Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine; it typically includes boiled eggs and can be smooth or chunky. If you’ve got a craving for chopped liver, check out Tori Avey’s Chopped Liver recipe on her website.

Chopped liver is part of Jewish culture as I learned in the hilarious and educational book, The Big Jewish Book for Jews: Everything You Need to Know to Be a Really Jewish Jew by Ellis Weiner and Barbara Davilman. They say, “Anyone seeking to upgrade his or her Jewishness should learn to love chopped liver, and if they already love it, to make it.”

[I highly recommend this book; it’s so funny.]

What is forcemeat?

Let’s go back to Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition for the definition of forcemeat. In the glossary, the Culinary Institute of America defines forcemeat as, “A mixture of chopped or ground meat or seafood and other ingredients used for pâté, sausages, and other preparations.”

However, they do a better job of describing forcemeat in the main text. They say, “A forcemeat is a lean meat and fat emulsion that is established when the ingredients are processed together by grinding, sieving, or puréeing. Depending on the grinding and emulsifying methods and the intended use, the forcemeat may have a smooth consistency or may be heavily textured and course. The result must not be just a mixture but an emulsion, so that it will hold together properly when sliced.”

So, basically, forcemeat is meat stuffing that can turn into a sliceable product.

Let’s take a closer look at why forcemeat works as it does.

About fat, myosin and emulsions in forcemeat

Fat is an essential ingredient in forcemeat dishes and comes in the form of fatty meat or pure fat, like pork fat back.

In a forcemeat dish such as pâté, the fat and meat are ground (sometimes more than once) and then mixed with the other ingredients. Not just a quick stir; instead, the mixture is worked, either by hand or by using a stand mixer with a paddle attachment.

The reason for working the mixture (while being careful to keep all ingredients properly chilled) is to develop the myosin, which is a protein in meat. The myosin, when developed, becomes sticky and acts as a binder which is helpful when you’re making a sliceable pâté.

The binding properties of myosin is one thing that keeps the emulsion from breaking.

An emulsion is when two types of ingredients that don’t usually mix are mixed together to become one texture. For example, oil and vinegar separate quickly. But if you add some mustard—an emulsifier—to the mix, your dressing doesn’t separate into its main components.

Other names for forcemeat

Forcemeat is also known as farce. In their book, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie, Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman say, “[Forcemeat] began, apparently, as farce meat, meat that is to be used as a stuffing (ground meat that is to be pumped into casings, for instance), and evolved into forcemeat.”

Examples of forcemeat foods

Forcemeat foods include pâtés, terrines, mousselines and mousses (made of meat, not the dessert kind), sausages, stuffing, meatballs, cured meats like mortadella and bologna, meatloaf, galantines, ballotines and quenelles.

You can use forcemeat to stuff ravioli, dumplings, won tons, cabbage rolls, etc.

[By the way, if you want to know more about forcemeat, check out my article, Forcemeat 101: A Beginner’s Guide to Meat Emulsions.]

What’s the difference between pâté and forcemeat?

The differences between pâté and forcemeat include what they are, the purpose, ingredients, and the equipment required.

The differences between pâté and forcemeat

| Pâté | Forcemeat | |

| What it is | Ground meat and fat cooked in a terrine dish. A spreadable liver paste. | A ground meat and fat mixture; the main ingredient for pâtés, sausages, mortadella, etc. |

| The purpose | To turn meat and fat into a delicious, cold and enjoyable meatloaf that seems fancy because it’s French. | To be stuffed into other items, such as in sausages, galantines, ballotines and quenelles. To make meat and fat delicious together. |

| Ingredients | Pork and other meats such as duck, rabbit and game. Liver. Spices and/or aromatics. Port, brandy or wine. Stock. Heavy cream. Eggs. Butter. Bacon, caul or fatback. Lard, duck fat or butter to create a fat seal. Breadcrumbs and milk. | Similar to pâté ingredients but varies depending on the forcemeat dish and recipe. For example, meatloaf contains ketchup (gasp!) but that wouldn’t be in other forcemeat recipes. |

| Equipment | Terrine mold. Food processor or blender. Tamis or strainer. Meat thermometer. Roasting pan. Measuring equipment (including a scale). Sharp knife, bowls, utensils. Meat grinder (optional). Stand mixer with paddle attachment (optional). Instant-read or infrared thermometer (optional). | Depends on recipe but may include: Food processor. Meat grinder. Stand mixer with paddle attachment. Tamis or strainer. Meat thermometer. Measuring equipment (including a scale). Sharp knife, bowls, utensils. |

Bonus section: The link to my favourite chicken liver pâté recipe

As promised, I’m sharing my favourite chicken liver pâté recipe with you here. Because after all this talk about pâté (and forcemeat), you might have a hankering for some!

Chicken Liver Parfait from World Food Tour – This recipe is based on Jamie Oliver’s chicken liver pâté recipe. I do a couple things differently than the recipe calls for but it’s such a flexible recipe, it’s always delicious if you follow the main principles. [I did follow it exactly (except the olive oil) the first time.]

How I adjust this recipe:

- I use lard instead of olive oil.

- Last time I used pork liver instead of chicken liver (I was hesitant, but it turned out great).

- I don’t clarify the butter or use butter on top as a seal.

- I put the FULL amount of butter in the pâté instead of setting some aside for the top.

- I use melted lard as the fat layer.

- I strain it through one of my crappy strainers (not a tamis) because that makes all the difference (to me) between yucky and yummy pâté.

With all these changes, is it really my favourite recipe? Well, I’ll let you decide on that!

Conclusion

Well, that’s all for now folks. Pâté is forcemeat but forcemeat is not necessarily pâté. They’re both ways to enjoy delicious and nutritious meat. May your pâté taste like a work of art and may all your forcemeat dishes always keep their emulsions!