Confit and pâté are foods from the craft of charcuterie. But what exactly are they and what makes them different? If those questions are on your mind, you’ve come to the right place as I’ve put together this helpful article to cover these questions and more.

So…what’s the difference between confit and pâté?

Confit and pâté are foods in the realm of charcuterie. Confit is meat—generally poultry or pork—slow cooked in fat (lard, duck or goose fat), that can be preserved for months or even years. Pâté is a meat and fat mixture (forcemeat) cooked until firm and sliceable, also called pâté en terrine and terrine. The term pâté is also used for liver spreads such as liver mousse, chopped liver and chicken liver pâté.

Now you know the basic differences, let’s look at more details on what confit and pâté are, what foods can be confited and the differences between confit and pâté. And for a bonus, I’ll tell you what chopped liver can do for you, besides just being a delicious snack. But first, let’s get one definition out of the way…

What is charcuterie?

I mentioned confit and pâté fall under the realm of charcuterie. But what is charcuterie other than a French word with many syllables?

In Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, The Culinary Institute of America defines charcuterie as, “The preparation of pork and other meat items, such as hams, terrines, sausages, pâtés, and other forcemeats that are usually preserved in some manner, such as smoking, brining, and curing.”

What is confit?

In French, confit means to preserve. We’ve adopted this French word in English and use confit to describe the cooking method and the final preserved product. (Confit is pronounced con-fee and confited (as in the anglicized, “What meat can be confited?”) is pronounced con-feed.)

The confit cooking method is when you slow cook meat—typically poultry or pork—in animal fat attached to the meat and additional fat (as necessary) such as duck or goose fat or lard.

Fatty birds such as duck and goose and fatty cuts of pork can be cooked in their own fat. Leaner birds and pork cuts need additional fat.

According to Anne Willan, in her 1981 book, Regional French Cooking, “Goose is normally cooked in goose fat, which can be bought in tins, duck in duck fat and pork in lard. However, lard can be used for everything, or fat left from previous confits can be reused after straining, although after three or four cycles it becomes too salty.”

The basic confit process is:

- Marinate the meat for eight hours to three days with salt and other aromatics.

- Put the meat, additional fat (as necessary) and a bit of water, stock or wine in a pot that’s small enough so the meat fits snugly.

- Cook low and slow for a few hours until the fat is clear and the meat sinks to the bottom.

- Store the meat in glass jars and cover entirely with fat to keep the air out.

- Enjoy your confit in the coming weeks and/or months.

During slow cooking, the water in the meat and skin evaporates and the gelatinous bits from the skin and bones separate from the cooking fat. The meat retains its flavour during this cooking process.

Confit has been used to preserve meat for hundreds of years—no refrigeration or canning methods are required. Though if you have a fridge, you can feel free to keep your confit in it, of course.

[For more information on confit cooking, check out my epic article, Confit: Preserving Yummy Meats the French Way. And if you’re wondering if this fatty style of cooking could possibly be good for you, have a look at another one of my articles, Is Confit Cooking Healthy? The Pros, Cons & Alternatives.]

What foods can be confited?

Confit isn’t for everything, but you can make a small variety of foods incredibly delicious with this cooking method.

Foods best suited to confit cooking:

- Duck legs.

- Chicken legs.

- Turkey legs.

- Goose legs.

- Legs of any poultry.

- Wings of any poultry.

- Poultry gizzards.

- Pork loin.

- Pork belly.

- Pork shoulder.

- Any part of the pig!

- Vegetables including squash, tomatoes, cauliflower, onion, garlic, etc. (Confit vegetables aren’t a true confit as they’re typically simmered in olive oil (not animal fat) and they only keep a couple weeks in the fridge.)

We often think of confit as duck legs, but that limited thinking leaves us without the wonders of pork confit.

In their book, Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking & Curing, Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn say, “Pork is excellent for confit … Actually, any part of the pig can be confited with excellent results. Confited belly and shoulder are rare treats in the home kitchen, extraordinary for their succulence and flavor.”

What is pâté?

Pâté is simply meat and fat ground and mixed into a paste and cooked. If this pâté is cooked in a terrine—and it often is—we call it pâté en terrine or just pâté or terrine for short. If this pâté is cooked in pastry, it’s called pâté en croûte, even in English. These French terms are all used in English culinary vocabulary. (Pâté translates into paste so you can see why we use the fancy French word instead.)

Pâtés are generally made of pork or pork and other meats including game. For texture and design, they’re often made with structured inlays (large pieces of meat) or interior garnishes which are smaller chunks of meat, pistachios, dried fruit, etc.

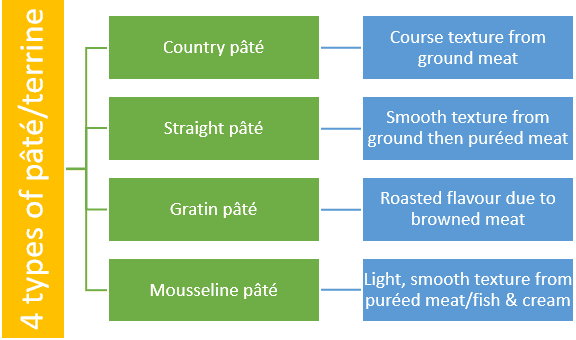

There are four classifications of pâtés: straight pâtés, country pâtés, gratin pâtés and mousseline pâtés.

Diagram: Pâté classification

These pâtés are all firm and sliceable and they may or may not contain liver.

Common pâté ingredients include:

- Pork and other meats such as duck, rabbit and game.

- Liver.

- Spices and/or aromatics.

- Port, brandy or wine.

- Stock.

- Heavy cream.

- Eggs.

- Butter.

- Bacon, caul or fatback.

- Lard, duck fat or butter to create a fat seal.

- Breadcrumbs and milk (for a panade).

What is spreadable liver pâté?

In North America and the United Kingdom, when we’re eating a spreadable liver paste (ewww), we call it pâté, liver pâté, chicken liver pâté, chicken liver mousse or chopped liver, depending on the recipe.

Liver is not optional in this type of pâté. It’s generally the only meat in the recipe and should be accompanied by a generous amount of butter and/or heavy cream.

The two main differences between chicken liver pâté and pâté en terrine are:

- One is spreadable, one is sliceable.

- Chicken liver pâté (or pâté made with any type of liver) is cooked on the stove top then blended up. Pâté en terrine is mixed and then cooked in the oven in a bain marie (water bath).

Chopped liver, a liver dish common in Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine that typically includes boiled eggs, can be smooth like chicken liver mousse or left quite chunky. If you’ve got a hankering for chopped liver, check out Tori Avey’s Chopped Liver recipe on her website. Plus, in this recipe, you get to discover (like I did) what gribenes are.

Bonus: What chopped liver can do for you besides fill your belly

For a cultural perspective on chopped liver, let’s look at what Ellis Weiner and Barbara Davilman have to say in their hilarious and educational book, The Big Jewish Book for Jews: Everything You Need to Know to Be a Really Jewish Jew. They say, “Chopped liver occupies a paradoxical place in Jewish culture as something both highly cherished and synonymous with irrelevance. Jews talk about chopped liver as though it were the apex of the Eastern European and Russian culinary tradition.”

But it’s also used to deflect an insult or slight. As in, “What am I, chopped liver?”

Ellis and Barbara say that “Anyone seeking to upgrade his or her Jewishness should learn to love chopped liver, and if they already love it, to make it.”

Great advice for Forcemeat Academy readers too! [Making chopped liver is on my to-do list, and I’ve already procured the schmaltz and chicken skin.]

What’s the difference between confit and pâté?

The differences between confit and pâté include what they are, ingredients, equipment required, temperatures and time.

The differences between confit and pâté

| Confit | Pâté | |

| What it is | A cooking method and the result of that cooking method. | Ground meat and fat cooked in a terrine dish. A spreadable liver paste. |

| Ingredients (not all ingredients listed are required for all recipes) | Meat (poultry legs, wings and gizzards or pork belly, shoulder, ribs and any other part of the pig). Fat (lard, duck or goose fat). Spices and aromatics. Water, stock or wine. | Pork and other meats such as duck, rabbit and game. Liver. Spices and/or aromatics. Port, brandy or wine. Stock. Heavy cream. Eggs. Butter. Bacon, caul or fatback. Lard, duck fat or butter to create a fat seal. Breadcrumbs and milk. |

| The purpose | To cook meat until tender and preserve it in its own fat. | To turn meat and fat into a delicious, cold and enjoyable meatloaf that seems fancy because it’s French. |

| Equipment | A pot. The oven. A knife for cutting the meat. | Terrine mold. Food processor or blender. Tamis or strainer. Meat thermometer. Roasting pan. Measuring equipment (including a scale). Sharp knife, bowls, utensils. Meat grinder (optional). Stand mixer with paddle attachment (optional). Instant-read or infrared thermometer (optional). |

| Cooking temperatures | Low oven temperature: 200°F (93°C) to 300°F (150°C). | Higher oven temperature for the water bath: 300°F (150°C). |

| Preservation method? | Yes. | No. |

| Cooking time required | Two to six hours. | 45 to 90 minutes (depending on your recipe, of course). |

Conclusion

Well, that’s it for now folks. Confit and pâté are both delicious foods from the French world of charcuterie and worth exploring as home cooks. May your confit be tender and plentiful and may your pâté be elegant, delicious and satisfying!