Chicken liver pâté isn’t for everyone but the smoother and creamier it is, the more likely people will love it. However, grainy and gritty chicken liver pâté disappoints even the most fervent chicken liver pâté fan. Today, I’m talking about why chicken liver pâté becomes grainy and several ways you can avoid this dire situation.

Let’s get straight to the goods…why is your chicken liver pâté grainy?

Chicken liver pâté turns out grainy when the liver is overcooked, when the pâté isn’t strained through a tamis or mesh sieve and/or when there’s not enough fat—such as butter, schmaltz, pork fat or duck fat—in the recipe. Grainy liver pâté is more common when the liver is cooked on the stovetop rather than when the pâté is cooked in the oven in a water bath.

Now you know the reasons behind sad, grainy pâté, let’s dive into each of these items further to assure that grainy pâté never happens to you and your family again. Amen.

By the way, though this article is about chicken liver pâté (the spreadable kind), these tips apply to liver pâté made from any type of liver, including pork, beef, venison, rabbit, etc.

Tip #1 for avoiding grainy liver pâté: Do not overcook the liver

Overcooking liver makes liver rather unpleasant to eat, whether you’re making some liver and onions or a chicken liver pâté. However, it seems that headlines like this one from The Daily Mail—Why chicken liver pate could be the most dangerous dinner party dish: Rates of food poisoning soar due to ‘undercooking’ trend—have pushed folks in the opposite direction. Nobody wants to undercook liver to the point of poisoning dinner guests but are we erring on the side of overcooking liver? With grainy results???

I’ve never been a liver lover and I hadn’t read any articles about food poisoning the first times I made chicken liver pâté, so I wasn’t tempted to overcook them. However, during my first attempt at chicken liver pâté, I erred on the side of undercooking—which made my pâté taste too “livery.” So, I learned my lesson.

In terms of doneness, there are three basic ways to go with liver: overcooked, too pink and just pink enough. With chicken liver pâté, you’re striving for just pink enough. Overcooking is when the liver is brown all the way through. Too pink is when the liver is red throughout.

Just pink enough method #1: poaching

Just pink enough is a fine line between the other two options. Fortunately, Talia Lavin, in her Bon Appetit article called, How to Make Pâté at Home and Be a Person Who Eats Liver, tells us how to achieve this and her approach is a little different than you’ll find in many recipes.

Talia recommends frying your onions and seasonings, then adding balsamic vinegar, wine and liver to the pan, all at once. Most recipes call for searing the livers before deglazing the pan with the wine and vinegar. With Talia’s method, you’re not frying the livers but poaching them gently in liquid.

Talia says, “Let the livers brown in the liquid, turning them over with a spatula so that both sides are an even color, and the insides remain slightly pink, about two to three minutes on each side. The aroma in your kitchen should be sharp, meaty, with an alliaceous kick…Turn off the burner and let the livers stand in the liquid for a few minutes, until the liquid has stopped bubbling and cooled slightly…My experiments have indicated that this is the perfect amount of time before the next step.”

Just pink enough method #2: frying or searing

However, if you don’t want to use this poaching approach, you can also sear the liver(s) before deglazing the pan.

Pinehurst, a commenter on the Chowhound forum post called How do you tell when liver is done?, says, “Overcooked beef liver is not tasty, as you know. My rule is for every ½ inch slice, 2 minutes on the first side, 1.5 min on the second side, medium high heat, fried in bacon drippings (and plenty of it). It cooks very quickly.”

This is a great tip but with a few more details, you can get the whole picture.

In Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, The Culinary Institute of America talks about how to sear meat properly. They say, “The best way to accomplish this is to work in small batches and to avoid crowding the meat in the pan.” This is the advice they give for searing meat for gratin pâtés, but it applies to cooking liver for liver pâté and complements the timing advice given above.

Bonus question: But is it safe to eat pink liver?

In their book, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie, Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman say, “The quality of the livers is paramount. If you have access to local, farm-raised chickens, ask the farmer for the livers. Standard commodity livers offered in the grocery store are of uneven quality. High-quality livers can be eaten medium-rare.”

That’s the chef perspective, which is probably a little different than the perspective of the public health department.

If you’d like to know more about liver and food poisoning, check out my article Is Pâté Raw? No, Unless Undercooked Liver Qualifies and scroll down to the section called the connection between pâté and food poisoning.

Tip #2 for avoiding grainy liver pâté: Strain your pâté

The first time I read a chicken liver pâté recipe that called for straining the pâté, I balked. I mentally categorized it as one of those unnecessary steps in the kitchen. This is probably because I prefer a less-is-more style of cooking.

However, when I was making the recipe, I reconsidered. I had already done the disgusting work of cleaning and trimming the chicken livers … so is straining the pâté that much worse? Plus, when I make a new recipe, I follow the recipe as closely as possible to get a feel for it.

So, I strained my chicken liver pâté … and it was amazingly smooth!

I became an instant straining-liver-pâté convert!

Why strain your liver pâté and with what?

Straining your liver pâté makes it smooth and removes all the icky bits that are invisible to the eye. Seriously, when you clean your strainer, you’ll wonder what all that stuff is.

The best way to strain your liver pâté is with a tamis (pronounced ta-mee). A tamis is a fine-meshed drum sieve that looks like a tambourine (no jingle attachments though). The mesh can be made of stainless steel or nylon and comes in three sizes, often referred to as course, medium and fine.

According to the MTC Kitchen site, on their product description for the Tamis Mesh Screen Uragoshi for Sieve Frame, “The mesh size indicates the number of openings in one inch of screen. So a 20 mesh screen means there are 20 squares across one linear inch of screen. A larger mesh size means a finer mesh.” This product is made in Japan and the three mesh sizes are referred to as 20 (coarse), 30 (medium) and 50 (fine).

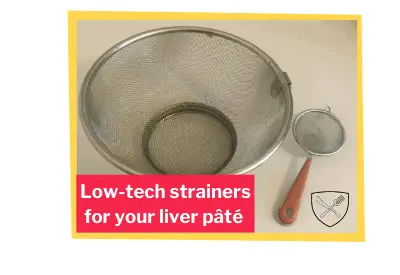

You don’t have to buy a tamis for your liver pâté; you can also use a regular strainer, either one with a rounded bottom or, if it’s all you have, one with a base on the bottom.

Right now, I have a small, cheap strainer and a bigger colander-style strainer and they do an adequate job straining the pâté. Actually, I never say, “Gosh, I wish this pâté was smoother,” so maybe they do an awesome job! [I generally use the small one because the big one (with the base) has more areas to clean which annoys me.]

At what point do you strain the pâté?

For chicken liver pâté that you’re making on the stove, most recipes call for straining the final product after all the ingredients are added and puréed.

However, I don’t do it this way. Perhaps because of my tiny strainer situation, I generally strain before all the ingredients are blended up. I blend up the liver with the deglazing ingredients, then I strain that. This means I have to force a smaller amount of goop through my tiny strainer. Once it’s strained, I put blend this strained mess with the remaining ingredients (which, at that point is mostly butter).

[Also, as I write this, I use either the immersion blender or the Magic Bullet to blend my liver pâté and neither option is as good as a blender or food processor. Talk about a sub-par set-up!]

I also do this for my favourite pâté called Chicken Liver Terrine (which is on page 59 of the amazing book, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie by Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman). This recipe is mostly heavy cream and wine with a little bit of liver and it works well when I strain the liver mixture before I add the TWO CUPS of heavy cream to the mix. (More on this type of liver pâté recipe in tip #4.)

All this to say, strain your pâté! If I do it, you can too. It really doesn’t take much time and if you have a decent sized strainer, it should only add a few minutes to your pâté-making time. Well worth it!

Can this tip save too-grainy pâté?

If you’re looking at a batch of pâté that’s too grainy/gritty, straining it can help, even if you overcooked the liver. For your best chance, add some more fat (see tip #3) and strain it. If that doesn’t work, eat the pâté on a sandwich or in a wrap so the grainy texture is hidden by all the other ingredients.

Tip #3 for avoiding grainy liver pâté: Be generous with the fat

Using too little fat can make your liver pâté grainy; instead, use a generous amount of fat. This can be butter, lard, duck fat or chicken fat (schmaltz).

But what is a generous amount of fat?

It’s common for chicken liver pâté recipes to call for about a pound (454 grams) of chicken liver. If this is the case, aim for about two thirds of a pound of butter (300 grams).

The amount of fat you use should make you pause and think, “Is that too much?” If the chunk of butter you set aside for the pâté doesn’t inspire this question, it’s not enough.

Hints that you have an inappropriately low-fat chicken liver pâté recipe:

- The butter (or other fat) is measured in tablespoons (rather than fractions of a pound or kilo).

- Your recipe calls for stock or water. Now, stock isn’t bad per se, but I’ve noticed that recipes that call for stock or water also tend to skimp on the butter. Acceptable liquids for chicken liver pâté are booze and/or heavy cream (alcoholics can use stock, of course, but please stick to yummy, recipes with a high-fat ratio, as I recommend for everyone).

Recipe suggestion for chicken liver pâté that uses a good amount of fat

Chicken Liver Parfait from World Food Tour – This recipe is based on Jamie Oliver’s chicken liver pâté recipe. It uses 400 grams of liver and 300 grams of butter which is great. Except the recipe suggests setting aside part of that butter to melt on top of the pâté once it’s in jars. I prefer using ALL the butter IN the pâté and melting some leftover bacon grease to use as the fat topping.

I use all the butter in the pâté for two reasons:

- It makes the texture of the pâté smoother (more butter = more better).

- The lard/bacon grease is a softer fat than clarified butter, which makes for a better user experience when cracking into the jar of pâté. The clarified butter top cracks when you put a knife to it (when it’s straight out of the fridge). However, with the lard topping, a butter knife slides right through it.

[By the way, if you’re wondering if all this animal fat is gonna be the death of you, check out my article, Is Forcemeat Healthy? 16 Answers According to Popular Diets.]

Tip #4 for avoiding grainy liver pâté: Try a recipe that calls for cooking the pâté in a water bath in the oven

There are two ways to cook chicken liver pâté. As we’ve already discussed, the most common way is on the stove top. This is when you cook the liver and aromatics on the stove top before blending all the ingredients with a food processor.

The other way is in a water bath (also known as a bain marie) in the oven. With this method, you blend all the raw ingredients in the food processor and then pour the mix into a terrine. Then you put the terrine in a larger, oven-safe dish that’s partially full of water (the water bath) and put it all into the oven to cook. The water bath provides a gentle cooking, away from the extreme heat of the oven air.

Kyle Hildebrant, in his food blog, Our Daily Brine, talks about these two cooking methods in his article (and recipe) called, Chicken Liver Mousse Pâté with Port Gelée. He says that cooking the liver on the stove is perceived as easier and can give the pâté a robust flavour. But the stove top method can also leave your pâté with a gritty texture, even if you have a deluxe high-speed blender.

Using this oven method gives the pâté a silky texture and leaves the pâté slightly pink (rather than brown), especially if you add some Insta Cure #1. Plus, it’s easy.

The Chicken Liver Terrine recipe I mentioned earlier uses the oven method and it’s so delicious! The texture is like a dessert mousse (take this description with a grain of salt as I haven’t eaten sweets in years so this could be very wrong for most people but it’s true for me).

Also, if you haven’t purchased Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie by Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman, and you love pâté, I encourage you to do so. It’s amazing. (You can get it on Amazon here.)

Conclusion

Well, that’s all I have to say about grainy pâté for now folks. You now have four tools in your toolbox for smooth, creamy chicken liver pâté and success will be yours. May your chicken liver pâté be smooth, buttery and perfectly delicious always!