When I first came across the term forcemeat, I had no idea what it was. Nor did I know that my favourite delicacies—chicken liver mousse and good ole sausages—fell under the category of forcemeat. So, I wanted to put together a comprehensive article about everything you could possibly want to know—in general—about forcemeats as a home cook and beginner forcemeat enthusiast.

This beginner’s guide to forcemeat covers these topics:

- What is forcemeat?

- What is an emulsion?

- Where does the word forcemeat come from?

- What are the four types of forcemeat and what makes them unique?

- What are examples of forcemeat foods?

- Why make forcemeat foods?

- What ingredients are used in forcemeats?

- What are standard forcemeat ratios?

- What’s the 5/4/3 emulsion?

- What binders are used in forcemeats?

- Why is salt important in forcemeats and how much is required?

- What is curing salt, and do I have to use it in forcemeats?

- What’s the difference between forcemeat and garde manger?

- What does grinding do for forcemeat?

- What are the types of forcemeat grinds?

- Why is it important to keep forcemeat ingredients chilled?

- What equipment is necessary for making forcemeats at home?

Now that it’s obvious that one question quickly leads to another when it comes to learning about forcemeats, let’s dig into them, one answer at a time!

Section 1: What is forcemeat?

Dictionary.com indicates forcemeat is a cookery noun and defines it as, “a mixture of finely chopped and seasoned foods, usually containing egg white, meat or fish, etc., used as a stuffing or served alone.”

That’s fine for a beginner definition, but let’s move into a culinary definition suitable for a home cook who’s getting into forcemeat.

In Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, The Culinary Institute of America, gives a precise definition of forcemeat. They say, “A forcemeat is a lean meat and fat emulsion that is established when the ingredients are processed together by grinding, sieving, or puréeing. Depending on the grinding and emulsifying methods and the intended use, the forcemeat may have a smooth consistency or may be heavily textured and course. The result must not be just a mixture but an emulsion, so that it will hold together properly when sliced.”

Much more detailed, thanks CIA! (Yes, it’s common to shorten the Culinary Institute of America to CIA, which amuses me.)

Section 2: What is an emulsion?

As you gleaned from the Garde Manger definition, an emulsion is an essential component of forcemeat. An emulsion is when two types of ingredients that don’t usually mix are mixed together to become one texture. For example, an oil and vinegar dressing separates quickly after you shake it up. But if you add a little mustard to the mix, it acts as an emulsifier and your dressing doesn’t separate into its main components.

In forcemeat, the separate components are lean meat and fat (and sometimes liquid) and the emulsifying happens because of the mixing methods and the ingredients. For example, meat has a protein called myosin which becomes sticky when it’s worked (as it is with grinding, mixing and puréeing). This stickiness is a natural binder, but more on binders later.

Section 3: Where does the word forcemeat come from?

Forcemeat is a strange word, isn’t it? Especially because the forcemeat emulsion is a rather gentle process—there’s no forcing meat together! The word forcemeat originates from the French verb farcir, which means to stuff. Merriam Webster suggests that the French borrowed this verb from the Latin facire, which also means to stuff.

You might also come across the word farce used as a verb and noun. In the culinary sense, farce means to stuff and it can be the stuffing itself. In the glossary of Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, farce is referred to as forcemeat or stuffing.

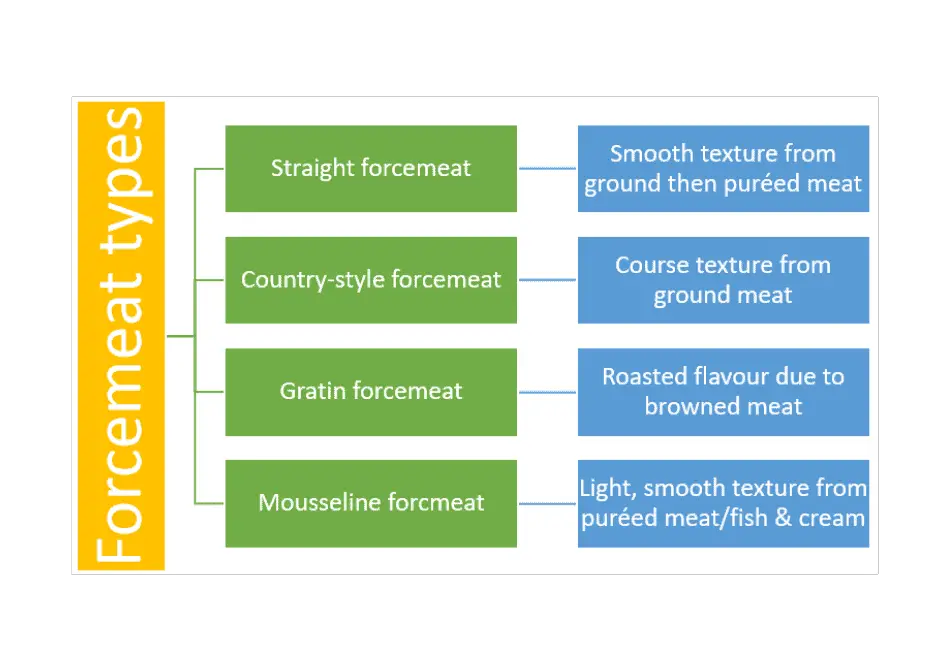

Section 4: What are the four types of forcemeat and what makes them unique?

There are four types of forcemeat: straight, country-style, gratin and mousseline and they’re all a bit different.

Straight forcemeat

Straight forcemeat has a smooth texture due to a two-step grinding process; the meat and fat mix is first ground, then puréed.

Country-style forcemeat

Country-style forcemeat has a chunky texture. The meat and fat mix is ground to a courser texture and not puréed like a straight forcemeat recipe. According to Wayne Gisslen in his book, Professional Cooking, College Version, Seventh Edition, country-style forcemeat is not its own type. He puts it in the straight forcemeat category as only the texture is different.

Gratin forcemeat

With a gratin forcemeat, part of the meat is seared and cooled before grinding. Searing adds a deeper flavour, but this partial cooking means the meat doesn’t bind together as well as the mixed raw meat and fat. For this reason, gratin forcemeats are also made with cream, eggs, milk and/or breadcrumbs which are binders (more on that shortly).

Mousseline forcemeat

Mousselines are made with any white meat or seafood, plus cream and egg whites. The meat or seafood is either ground in a grinder or mixed in a food processor, depending on how dense the meat is. For an extra smooth mousseline, the mix is strained through a tamis or fine-mesh strainer.

Section 5: What are examples of forcemeat foods?

Forcemeat foods include pâtés, terrines, mousselines and mousses (made of meat, not the dessert kind), sausages, stuffing, meatballs, meatloaf, galantines and quenelles.

[At Forcemeat Academy, we also branch into the world of charcuterie and French country cooking that includes fatty delights like rillettes, confit, rillons, smoked meats, etc.]

Section 6: Why make forcemeat foods?

Forcemeat dishes are tasty and if you follow simple recipes, they’re fairly easy to make and they look like you slaved away in the kitchen all day! If you stay away from dining on grade A fois gras pâté or terrines that feature smoked duck breast inlays, they can also be an economical dish that feels decadent.

If you’re on a high-fat, animal foods diet (for example, keto, carnivore, Zero Carb), forcemeat foods fit right in. As do many of the meat-based dishes found in French country cooking.

Finally, making a pâté en terrine feels like a treat. You work hard, don’t you deserve a meaty treat this weekend? I know I do!

Section 7: What ingredients are used in forcemeats?

Forcemeats generally contain these ingredients:

- Pork, poultry or seafood (as one main meat).

- Another lean meat, including more pork, veal, poultry, rabbit, game, etc.

- Fat, usually pork fatback.

- Spices.

- Salt.

Forcemeats may contain these ingredients:

- Fish and/or seafood.

- Liver, including chicken, pork, beef, duck, rabbit, etc.

- Garnishes or inlays (for texture).

- Port, brandy or wine.

- Heavy cream.

- Butter.

- Eggs.

- Bacon, caul or thin slices of fatback.

- Milk.

- Breadcrumbs, bread or flour.

- Curing salt.

- Gelatin (for aspic).

- Ice, ice water or beer (for example, in sausage making).

Section 8: What are standard forcemeat ratios?

When you want to make pâtés (en terrine or otherwise), you can use small bits of meat and fat you have laying around (refrigerated, please) if you know the general ratios, which I’ve put below.

If you’re a beginner like me, you might want to stick to following recipes until you get such a feel for forcemeat that you can work with ratios rather than recipes.

| Type of forcemeat | Fat to lean ratio | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Straight Country-style | Option 1 giving you fat content of 40% to 45%[1]: 2 parts lean 2 parts fat 1 part pork shoulder 2% salt by weight Option 2[2]: 50% to 65% lean meat 35% to 50% fat Seasonings | Sausages Pâté en terrine Pâté |

| Gratin | Same as option 1 above with additional cream, eggs, and/or breadcrumbs as binders.[3] | Pâté en terrine Pâté |

| Mousseline[4] | 2 parts meat 1 part cream 1 egg white per pound | Pâté en terrine Pâté |

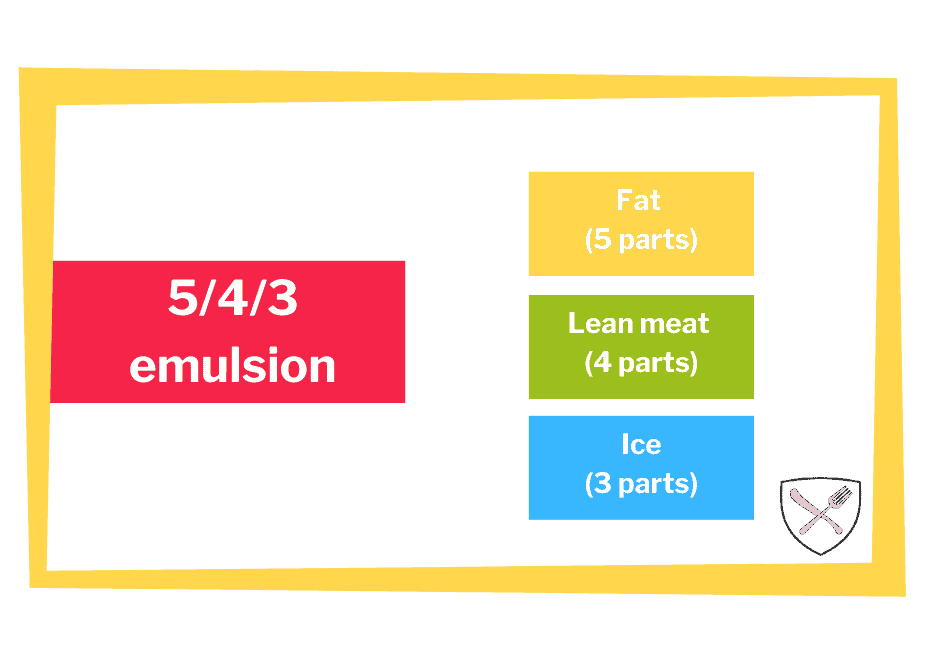

Section 9: What’s the 5/4/3 emulsion?

The 5/4/3 emulsion is the ratio of lean meat, fat and ice (or water) used for making sausages—possibly the most famous type of forcemeat to people who aren’t French. This 5/4/3 emulsion ratio is by weight and is also used for making bologna and hot dogs.

In this type of preparation, the meat and fat are ground in the meat grinder. Then the ground mixture and crushed ice are mixed further in a food processor. Some sausage recipes call for cold or icy water or beer instead of crushed ice.

Section 10: What binders are used in forcemeats?

As mentioned earlier, forcemeats are meat and fat emulsions, where all ingredients become one together. It’s easiest to think of a hot dog here. Many forcemeats rely on working the meat protein myosin (through grinding, mixing and/or puréeing) as the main binder. However, this isn’t always sufficient, depending on the recipe or type of forcemeat you’re making.

Forcemeat binders include:

- Eggs.

- Egg whites.

- Panades/panadas (made from bread/breadcrumbs/flour and milk or cream, can also be made from mashed potatoes or rice).

- Heavy cream.

- Gelatin.

- Dry milk powder.

- Boiled mashed potatoes.

- Rice.

Binders and their common forcemeat applications

| Straight | Country-style | Gratin | Mousseline | 5/4/3 emulsion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eggs | YES | YES | YES | NO | NO |

| Egg whites | NO | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Panades/panadas | YES | YES | YES | NO | YES |

| Heavy cream | YES | YES | YES | YES | NO |

| Gelatin | YES | YES | ? | NO | NO |

| Dry milk powder | NO | NO | ? | NO | YES |

Section 11: Why is salt important in forcemeats and how much is required?

Salt is important in forcemeats for flavour. Sounds obvious, but the reason salt needs to be emphasized is because many forcemeats are served cold or room temperature. When foods are hot, we’re more able to pick up on the salt flavour. But when they’re served cold, the salt flavour is muted.

In, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie, Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman recommend using “about 2 percent [salt] by weight” for forcemeat dishes you’ll serve cold (which is double what you’d probably use for food served hot).

Section 12: What is curing salt, and do I have to use it in forcemeats?

Curing salt is a preservative and colouring agent. It’s used in forcemeat dishes to make them last longer without spoiling and to keep (or create) a pink colour. (Like you know when your chicken liver mousse is pink in some areas and brown in other areas? And you think, “Should I eat that?” but you do anyway? You can guess that curing salt wasn’t used in that recipe.)

Curing salt is often used in charcuterie dishes that are brined, smoked or dry-cured and sometimes used in forcemeat dishes like sausages, pâté en terrine, etc.

Since we’re new to this game, I suggest we simply follow the recipes we use instead of adding or subtracting curing salts on a whim. This is especially good advice for making dry-cured charcuterie products (salami, pepperoni, etc.) because the curing salts keep botulism at bay—so using Insta Cure #2 in the right quantity is a food-safety issue.

Common curing salts are:

- Prague powder #1, also known as Insta Cure #1.

- Prague powder #2, also known as Insta Cure #2.

- Saltpetre

Curing salts and their uses

| Common name | Alternate name(s) | Ingredients | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insta Cure #1 | Prague powder #1 | Salt Sodium nitrite (6.25%) Anti-caking agent | General-use cure for meats that you cook, can, brine or smoke. |

| Insta Cure #2 | Prague powder #2 | Salt Sodium nitrite (6.25%) Sodium nitrate (1%) | For dry-cured charcuterie that are hung for months such as salami, pepperoni, prosciutto, etc. Insta Cure #2 keeps botulism at bay so it’s a food safety ingredient. |

| Saltpetre | Saltpeter Nitrate of potash | Potassium nitrate (KNO3) | Used historically to cure meat but not as reliable as other nitrate mixes. It may still be used in some charcuterie recipes. |

Bonus resource for sausage fans: The Sausage Maker Inc.

If you’ve found this article because sausages are your main interest, you’ll notice that I haven’t (yet) written much about sausages. You might want to visit The Sausage Maker Inc. for all your sausage-making needs. They are “the ultimate resource for hunters, gatherers, anglers, farmers and just about anyone else who likes to take game, meats, fruits and vegetables and transform them into the sausage, cider and vegetable recipes that have been handed down by generations of like-minded folks.”

Check out their Beginner’s Guide to Sausage Making.

Section 13: What’s the difference between forcemeat and garde manger?

In culinary terms, garde manger means cold kitchen. It’s a specialty area focused on serving cold foods, including appetizers, salads, cheeses, pâtés, charcuterie, pickles, etc. Forcemeat dishes are one element of the garde manger as they’re typically served cold.

“Garde Manger has evolved to mean more than just a storage area or larder. It also indicates the station in a professional kitchen responsible for preparing cold foods, the cooks and chefs who prepare these cold foods, and nowadays also an area of specialization in professional culinary arts. Members of today’s garde manger share in a long culinary and social tradition, one that stretches back to well before the dawn of recorded history.”

Garde Manger: The Art and Craft of the Cold Kitchen, Fourth Edition, The Culinary Institute of America

Section 14: What does grinding do for forcemeat?

As we discussed earlier, forcemeat is an emulsion of meat and fat so that by the end of cooking, the two ingredients become one. Grinding does two things: it helps make a stable emulsion (that doesn’t break) and it develops the protein myosin in the meat which acts as a natural binder. (This is why many forcemeat dishes don’t need other binders like bread, flour or eggs.)

There are generally two types of forcemeat recipes: ones that instruct you to grind your own meat and ones that call for ground meat. If you don’t have the equipment or constitution for grinding your own perfectly chilled meat, start with the recipes that call for ground meat. You can always move onto the more complex recipes later.

Section 15: What are the types of forcemeat grinds?

Forcemeat recipes typically call for grinding meat progressively, starting with a course grind.

Generally, you don’t stop there because further grinding is what develops the myosin and makes a good bind. There can be three stages of grinding which gives you course, medium and fine grinds.

For example, in a country-style pâté, the final texture is course. But as I just mentioned, coarsely ground meat doesn’t work the myosin enough for a good bind. To keep a course texture yet get a good bind, Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman say, “We regrind about a third of the meat through a fine die.” (From their book, Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie.)

Some recipes call for grinding the chilled meat and fat separately and some don’t. Follow the recipe for best results!

Grinder dies: Sizes and uses

| Grinder dies | Type of grind | Uses |

|---|---|---|

(3 mm) | Fine | Hamburger, hot dogs, pâté, etc. |

(4.5 mm) | Fine | Hamburger, sausage, pâté, etc. |

(6 mm) | Regular/medium | Course sausages, pâté, etc. |

| 3/8 (9 or 10 mm) | Course | The first grind, chorizo, pâté, etc. |

(12 mm) | Course | The first grind, stew meats, pâté, etc. |

A note about meat grinding blades and dies

Just like kitchen knifes, the blades in your food processor and meat grinder and the grinding dies themselves can get dull over time and sabotage the texture of your forcemeat dish. You can buy and use sharpening stones (like this one from the Sausage Maker) or take them to a local knife sharpener. Call ahead to make sure they sharpen grinding blades and dies.

Section 16: Why is it important to keep forcemeat ingredients chilled?

In many forcemeat recipes, you’ll see instructions for keeping the ingredients and the tools chilled. If you do a progressive grind, you’re often advised to put the coarsely-ground mix back in the fridge or freezer until it’s time to do the next grind. The grinder dies and feeding tube should be put in the fridge or freezer before you use them. And often, the bowl that catches your newly-ground meat sits in another bowl, which is full of ice.

Forcemeat and charcuterie enthusiasts are serious about staying chilly!

Keeping everything chilled is to get best results after cooking. If the meat and fat mix gets too warm during the grinding, the final product can break emulsification. This means the meat and fat separate and after the dish is cooked, the meat can become both dry and greasy, instead of smooth and satisfying. What a bummer!

How chilled is chilled?

In their book, Charcuterie: The Craft of Salting, Smoking & Curing, Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn say, “If you keep all your ingredients chilled, below 40 degrees F./4 degrees C., usually your meat and fat will combine perfectly.”

Section 17: What equipment is necessary for making forcemeats at home?

To make forcemeats at home, the equipment depends on the type of forcemeat dishes you’ll make. For example, making a pâté en terrine requires the same and different equipment as sausage making.

Equipment needed for making forcemeats includes:

- Food processor.

- Stand mixer with paddle attachment.

- Tamis or sieve (fine mesh).

- Meat grinder.

- Sausage stuffer.

- Terrine mold or loaf pan.

- Roasting pan (for the water bath).

- Instant-read thermometer.

- Bowls, pans and utensils.

Let’s look at what equipment you need for each type of forcemeat creation. Where you see Y/N, it means that sometimes you need them and sometimes you don’t.

Equipment for forcemeat making!

| Equipment | Pâté | Pâté en terrine | Mousseline | Sausages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food processor | Y/N | Y/N | YES | NO |

| Stand mixer with paddle attachment | Y/N | Y/N | NO | YES |

| Meat grinder | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | YES |

| Sausage stuffer | NO | NO | NO | YES |

| Tamis/sieve | Y/N | Y/N | Y/N | NO |

| Terrine mold | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Loaf pan | NO | NO | YES | NO |

| Roasting pan | NO | YES | YES | NO |

| Instant-read thermometer | Y/N | YES | YES | NO |

| Bowls, pans and utensils | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Equipment for forcemeats! | Meatloaf | Quenelles | Stuffing, meatballs | Galantine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food processor | NO | YES | Y/N | YES |

| Stand mixer with paddle attachment | Y/N | NO | Y/N | NO |

| Meat grinder | Y/N | NO | Y/N | NO |

| Sausage stuffer | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Tamis/sieve | NO | Y/N | NO | NO |

| Terrine mold | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Loaf pan | YES | NO | NO | NO |

| Roasting pan | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Instant-read thermometer | Y/N | YES | NO | YES |

| Bowls, pans and utensils | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Conclusion

So there you have it: A crash course on the topic of forcemeats. Each type of forcemeat is another complete world to explore so this guide is just the beginning!

[1] Source: Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie (Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman)

[2] Source: Professional Cooking, College Version, Seventh Edition (Wayne Gisslen)

[3] I couldn’t find a source with specific ratios for gratin forcemeat. If you know of one, please send it my way!

[4] Source: Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie (Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman) (Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman)