While I was investigating pâté, I came across the question of whether pâté has listeria and I wondered if that was a big concern and if it was a concern, was it a concern for most people? So, I researched the topic and wanted to share what I found with you! I’m providing a quick glance answer below and then digging into the details of pâté and listeria for the rest of the article.

Does pâté have listeria & should you fret about it?

Pâté, including liver pâté, is associated with listeria according to studies since the 1980s, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and governmental agencies including the National Health Service, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Government of Canada and the Australian Department of Health. Whether you should fret about pâté and listeriosis depends on your risk status; pregnant women, the elderly and people with a compromised immune system are at higher risk when it comes to the effects of listeriosis.

So, let’s get to it!

[Medical disclaimer: I’m not a doctor, nor do I play one on TV, and this information is not to be construed as medical advice. However, I’ve sourced all claims and recommendations from “official” sources such as governmental agencies, scientific studies and recall notices. With this information and free will, I’m certain you’ll be able to make the best choice for you and your family about the risks and rewards of eating pâté in the time of listeriosis.]

When we talk about pâté and listeria, what kind of pâté are we talking about?

Pâté is short for pâté en terrine, which is a forcemeat (meat and fat) cooked in a dish called a terrine. These pâtés may or may not contain liver and are generally firm enough to slice. This type of pâté is also called terrine.

We also think of pâté as liver pâté, which is a creamy liver spread, also called liver mousse and chopped liver. With this type of pâté, liver is the main (and mostly only) meat.

For this article, we’ll assume pâté means both types of pâté, the spreadable kind and the sliceable kind.

The three reasons for bundling all pâtés together for this discussion on listeria are:

- Some articles/studies don’t say what type of pâté they’re talking about.

- Some sources refer to both types—for example, the FDA mentions “Refrigerated pâtés or meat spreads” on their Listeria: Frequently Asked Questions page.

- Some sources refer specifically to the type of pâté sampled but their description leads one to think it could be either type. For example, in the study, The occurrence of Listeria species in pate: the Cardiff experience 1989, they say, “Samples of pâté were obtained from retail and distribution outlets throughout South East Wales between May and August 1989. The majority were cut slices from bowls or loaves from delicatessen display counters or unopened packets from refrigerated storage though some vacuum packed individual portions were also tested.”

Furthermore, we’re talking about manufactured pâtés in this article. This includes refrigerated pâtés and tinned/jarred pâtés. However, not all of the studies I mention in this article explicitly mention if they’re talking about tinned or refrigerated pâtés.

What is listeria, listeriosis and invasive listeriosis?

Listeria is the shortened name of the germ Listeria monocytogenes. When you get an infection caused by the germ Listeria monocytogenes, the infection is called listeriosis. If the listeriosis infection spreads beyond the gut, it’s called invasive listeriosis.

In this article, I quote a bunch of scientific papers; they shorten Listeria monocytogenes to L. monocytogenes.

Symptoms of listeriosis—when you don’t know you have it, but you just know something isn’t right—include fever and diarrhea. They can also include symptoms common in other food poisoning situations: nausea, retching and stomach cramps.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (sourced below) suggests that this type of passing listeriosis is “rarely diagnosed.” They don’t say why but my guess is it comes and goes quickly. (Plus, who can think of going to the doctor when glued to the toilet?)

Invasive listeriosis is the type of listeriosis that gets diagnosed. Symptoms of invasive listeriosis can show up as early as a day after infection or as late as 70 days after exposure.

When pregnant women have invasive listeriosis, they’re symptoms are typically mild, including a fever and aches and pains. [More on the risks of listeriosis for pregnant ladies in the high-risk category coming soon in another section. If you don’t want to read the rest of this article, just know this before you go: listeriosis is mild for pregnant ladies but can be deadly to their unborn child/fetus. So, it’s serious stuff.]

When the rest of the population gets invasive listeriosis, the symptoms can include the ones just mentioned for pregnant ladies and “headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, and convulsions.”

[Source for this summary of listeria and listeriosis: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.]

When did listeria become linked with food?

According to the paper History and epidemiology of listeriosis by H. Hof, published in FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology (April 2003), “From 1926 to 1950 only sporadic reports on Listeria were published resulting in only few well-informed specialists.” What wasn’t known about listeria lasted for several more decades.

This paper also says, “Another keystone in listeriosis research was the observation of Schlech et al. that a listeriosis outbreak in Halifax, Canada was transmitted via infected food, namely coleslaw. Although the oral route of infection was described in the original publication of Murray et al., L. monocytogenes was not included in the list of bona fide food-borne pathogens until this Canadian experience. Food-relatedness was confirmed in the 1980s by the occurrence of several other outbreaks in the USA and Switzerland, due to cheese.”

Why are pâtés linked with listeria?

Before we point fingers at pâté, let’s remember that one meaty “patient zero” was another, less-fancy type of forcemeat. Yes, that’s right, according the CDC, a deadly case of listeria was traced back to a hot dog in 1988.

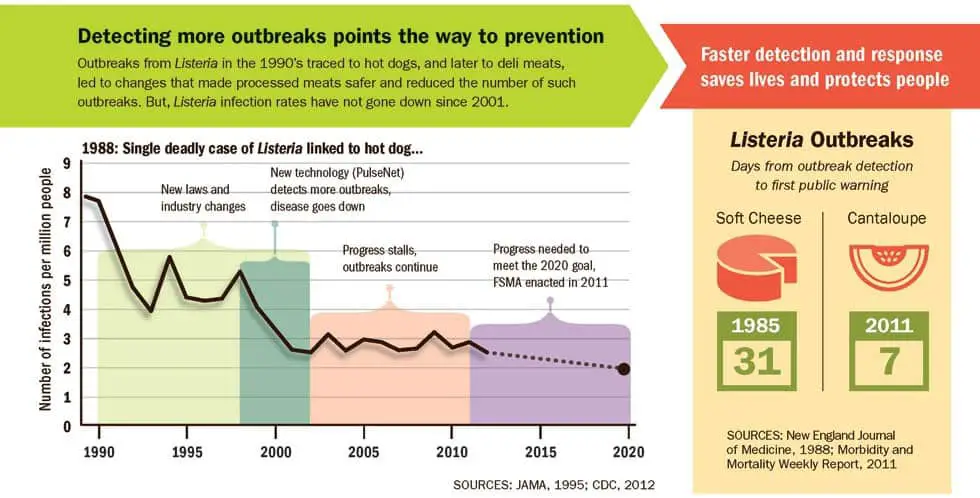

A history of listeria outbreaks

Infographic source: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/listeria/infographic.html

Alas, the association between pâté and listeria came not too long after the hot dog got famous for listeria.

I. J. Morris and C. D. Ribeiro showed in their paper, The occurrence of Listeria species in pâté: the Cardiff experience 1989., that of 216 pâté samples tested, “35% were contaminated with L. monocytogenes.”

In the paper, Human listeriosis and paté: a possible association., authors, J. McLauchlin, S. M. Hall, S. K. Velani and R. J. Gilbert, said “A survey of paté in England and Wales in July 1989 showed that it frequently contained L monocytogenes.” They concluded that, “Contamination of paté was a likely contributory cause of the increase in the incidence of listeriosis between 1987 and 1989.”

The first paper was about testing pâté samples only. The second paper tested pâté samples and included data from patients who tested positive for isolates of L monocytogenes. This data was obtained from “a standard questionnaire to obtain a food history covering the three weeks before onset of the illness. Information specifically on the consumption of pate was sought after mid-1989.”

So, the eighties really opened the world’s eyes to listeria infections in general and with listeria and pâté specifically.

[Bad news, pâté isn’t just associated with listeria. To see how pâté is associated with other food-poisoning bacteria like campylobacter, check out my article, Is Pâté Raw? No, Unless Undercooked Liver Qualifies, and scroll down to the section called, The connection between pâté and food poisoning.]

What listeria outbreaks are linked to pâté consumption?

Outbreak sounds big and bad, but you might feel relief when hear what the definition is. The CDC, in their Listeria Outbreaks article, says, “When two or more people get the same illness from the same contaminated food or drink, the event is called a foodborne disease outbreak.”

So, the threshold for an outbreak is rather low.

According to the paper, Listeriosis Outbreaks and Associated Food Vehicles, United States, 1998–2008 published in the Emerging Infectious Diseases journal, “Twenty-four confirmed listeriosis outbreaks were reported during 1998–2008, resulting in 359 illnesses, 215 hospitalizations, and 38 deaths. Outbreaks earlier in the study period were generally larger and longer … Ready-to-eat meats caused more early outbreaks, and novel vehicles (i.e., sprouts, taco/nacho salad) were associated with outbreaks later in the study period.”

Table 2 of this paper indicates that in 1999, there was a multi-state outbreak of listeriosis with pâté as the “food vehicle (reference).” Though this was a multi-state outbreak, there were only 11 cases.

So, one outbreak out of 24 was pinned on pâté in America. But the end point of that study was 2008 so what’s happening more recently with pâté and listeria?

What do recent studies say about pâté and listeria?

On the other side of the pond, in their study called, Human foodborne listeriosis in England and Wales, 1981 to 2015, the authors, J. McLauchlin, K. A. Grant, and C. F. L. Amar, say, “Between 1981 and 2015, 5252 human listeriosis cases were reported in England and Wales. The purpose of this study was to summarise data where consumption of specific foods was identified with transmission and these comprised 11 sporadic cases and 17 outbreaks. There was a single outbreak in the community of 378 cases (7% of the total) which was associated with pâté consumption…”

However, a closer look at their Table 4 reveals that the pâté outbreak happened between 1987 and 1989, because pâté tins/packs produced by “a single Belgian manufacturer were contaminated with L. monocytogenes.”

Two things to note about this study’s information:

- 50% of the pâté listeriosis cases were associated with pregnancy.

- This study references three other pâté and listeriosis studies, two of which I’ve referenced above and one which I couldn’t access (Listeria monocytogenes and pâté by the same authors as the Cardiff experiment mentioned above. It looks like it’s a letter to the editor, not another study.)

This study would be more interesting and relevant if we were looking at listeria outbreaks in general, not just for outbreaks associated with pâté.

Let’s move into the last few years.

In 2017, ResearchGate published, Local Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes Serotype 4b Sequence Type 6 Due to Contaminated Meat Pâté. This paper showed that in early 2016, there were five confirmed and two probable cases of listeriosis tied to pâté contaminated with L. monocytogenes. This happened in southern Switzerland. The pâté was from a manufacturing plant and listeria was found in the meat grinder—which caused the pâté to harbour the listeria bacteria.

Eurosurveillance, Europe’s journal on infectious disease surveillance, epidemiology, prevention and control published a 2019 study called, Listeriosis outbreak likely due to contaminated liver pâté consumed in a tavern, Austria, December 2018. The abstract of this study says in part, “In late December 2018, an outbreak of listeriosis occurred after a group of 32 individuals celebrated in a tavern in Styria, Austria; traditional Austrian food (e.g. meat, meat products and cheese) was served…Liver pâté produced by company X was identified as the likely source of the outbreak.”

Eleven of these party animals developed “gastrointestinal symptoms” and one person developed severe sepsis.

In the study, they report, “Through active case finding, we identified two more cases of invasive listeriosis.” These are folks who weren’t at the celebration mentioned above. One was an elderly person (early 80s) who regularly ate pâté from company X. This person died from the invasive listeriosis.

In their Listeria Outbreaks article, the Centers for Disease Control reports no listeria outbreaks in America related to pâté between 2011 and 2020. As I write this, the only listeria outbreak in America listed on their site was related to Enoki mushrooms. [Listeria knows we got other problems in 2020, ha ha.]

How common is listeria in pâté?

Healthline reports that listeria is found in pâté (and sliced meats) at a rate of zero to six percent. [They source this claim from four studies done between 2008 and 2015.]

Listeria is found in other foods so don’t take the pâté/deli meat rate and apply that to the overall risk of listeria contamination.

So, now that you know how common listeria is in pâté (and sliced meats), you probably want to know how to find out if your store-bought pâté might have listeria. The one sure way—though the information might come too late to matter—is through recall notices.

Where can I find pâté recall notices linked to listeria?

If you go looking for pâté recall notices, you may be surprised at how many you find. I was—there are a lot, even just in Canada.

Instead of telling you what pâtés were recalled, I’ll let you know where to find the recall notices. That way, you’ll always be able to access the most up-to-date information.

Where to find food recall notices: Canada

Go to the Food recall warnings and allergy alerts page on the Government of Canada website. You can then search by year and reason for recall. In the reason section, choose “Microbiological – Listeria.”

However, pâtés (and other foods) can be recalled for more than this one reason so to find the whole list, leave this field blank and just search for all recalls within the timeframe you’re looking at. Then do a Ctrl F (for “find” in your web browser) to search for pâté.

[You can see an example of pâtés being recalled for another reason in the Food Safety News article, Pâté recall for milk and soy allergens not declared on label.]

Where to find food recall notices: United States

Visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Listeria Outbreaks article to see their list of “Selected Multistate Outbreaks.” Plus, on the left-hand side of the page, you can search for outbreaks by food type, such as deli ham, pork products, frozen vegetables, cantaloupes, etc.

You can also see a list of recalls on the Recalls and Outbreaks page of the FoodSafety.gov website. This has a list of recalls in reverse chronological order (starting today) so that way of searching might be a bit better, depending on the search situation.

Where to find food recall notices: United Kingdom

Go to the Food Standards Agency Alerts page and search by food type. That was easy.

Where to find food recall notices: Australia

Go to the Food recalls page of the Food Standards Australia & New Zealand site. You can scroll by date or search the type of food you’re looking for. I did a quick test by searching for pâté and found the latest pâté recall was in 2018. Not for listeria though—for undeclared soy and dairy, which are classified as allergens.

Where to find worldwide food recall notices

If you’d like a world-wide list of food recalls every week, check out the eFood-Alert site published by Phyllis Entis, also known as the Food Bug Lady.

All these recall notices … is it just me or does it make you more committed to making your own pâté at home?!

How serious is listeria?

Earlier in this article, I mentioned the symptoms of listeriosis for pregnant women and everyone else. But the symptoms don’t tell you the whole story. So, let’s look at a few more things to help you get the big picture.

First, let’s look at the prevalence of listeriosis.

According to the CDC’s Questions and Answers page about listeriosis, “Every year, about 1,600 people get listeriosis in the United States.” This is a stat from 2016 but still, that’s quite recent.

In 2020, the population of the United States of America is about 330 million people. If you do the math, you’ll see that the odds of getting listeriosis are teeny-tiny. [The math: 1,600 cases divided by 330 million people x 100 (to get the percentage) gives you a 0.000484848485% chance of getting listeriosis by the numbers.]

Of course, your changes would go up if you’re eating only foods known for listeria. And I know that the arithmetic I did above is a very simple calculation that doesn’t take all the factors into it. But those two numbers should give you some perspective into the risk.

If you’re pregnant, ignore those last few sentences because there’s some special high-risk, bad news for you in the next section. Please read that.

Now let’s look at the severity of listeriosis for most people.

H. Hof in the paper, History and epidemiology of listeriosis, sums it up quite nicely by saying, “Nowadays it is well known that listeriosis is a foodborne disease. There is scant evidence that a mild and transient gastroenteritis may precede overt disease. Obviously, this exposure to pathogenic Listeriae is rather common, since more than 90% of adults possess immune lymphocytes. Whereas most normal, immunocompetent individuals will overcome an initial attack and shedding of Listeriae by feces is terminated after a few days, people at risk may suffer from disseminated infection.”

But invasive listeriosis—even though there aren’t too many cases every year, as noted by the USA stats earlier—is not so rosy.

And about the severity of this food-borne pathogen, the CDC Questions and Answers page about listeriosis says, “Most people with invasive listeriosis require hospital care, and about one in five people with the infection die.”

The symptoms associated with this disseminated infection—what we called invasive listeriosis earlier—include sepsis, meningitis, encephalitis and more.

People in a higher risk category include:

- Pregnant women.

- The elderly (more than 70-years-old).

- People with cancer, diabetes, leukemia, lupus, AIDS and iron overload.

- Alcoholics.

- People on steroid therapy.

- People who have had a kidney transplant.

This list of higher-risk people is from Table 2 in the History and epidemiology of listeriosis study.

Now let’s look at the risks for pregnant ladies.

What should pregnant women know about listeria?

Continuing with the History and epidemiology of listeriosis study, H. Hof does a great job explaining the dangers of listeriosis for pregnant women.

He (she?) says, “Pregnant women have a 12-fold increased risk in comparison with the normal population to acquire listeriosis after consumption of contaminated food. Although the mother herself will pass through a mild, flu-like, febrile episode, the pathogenic bacteria having access to the circulation will colonize the placenta, induce a placentitis and hence infect the defenseless fetus. Connatal infection will result in either stillbirth or early-onset listeriosis. The prognosis of this infection is rather poor.” [Emphasis mine.]

Now, let’s put this risk into a real-life scenario by looking at the results from a study called, Listeriosis outbreak associated with the consumption of rillettes in France in 1993. [We’ve veered off pâté and onto rillettes now, but the point here is about pregnancy and listeriosis, not about the source of the listeriosis.]

There were 38 patients who contracted listeriosis between June and October of 1993. Of these 38 patients, 31 were “materno-neonatal” (a.k.a. maternal-neonatal) patients: pregnant ladies and babies. The pregnant women ranged from 20 to 34-years old.

This outbreak had serious repercussions for the 31 materno-neonatal patients:

- Nine fetal deaths.

- 12 premature births, including five that were classified as severely pre-mature.

- One baby died at four-days-old.

- This outbreak had a case-fatality ratio of 32%.

I’m not one to whip people into a frenzy of fear but I believe it’s extremely important for you to know how devastating listeria is to fetuses so you can make an informed decision.

[To read more about listeria, pâté and pregnancy, check out my article, Is Pâté Safe During Pregnancy? What the Studies & Food Safety Experts Say.]

Can listeria be killed by cold temperatures, cleaning and cooking?

Have you ever seen Terminator 2? Where the old-fashioned T-800 puts enormous holes in the T-1000 with a shotgun and the T-1000 absorbs the damage and gets up to fight some more?

Listeria is kind of like the T-1000.

In their article, Listeria infection, The Mayo Clinic says, “Listeria bacteria can survive refrigeration and even freezing.”

It gets worse.

In the study, Short-term genome evolution of Listeria monocytogenes in a non-controlled environment, the authors say in their conclusion, “Our data support the hypothesis that the 2000 human listeriosis outbreak was caused by a L. monocytogenes strain that persisted in a food processing facility over 12 years…”

I’m sure that facility cleaned up quite a bit over 12 years and yet…

Well, now for the good news.

The US Food and Drug Administration, in their article, Get the Facts about Listeria, says, “Pasteurization, cooking, and most disinfecting agents kill L. monocytogenes. However, in some ready-to-eat food, such as hot dogs and deli meats, contamination may occur after the food is cooked in the factory but before it’s packaged. These products can be safely eaten if reheated until steaming hot.”

Steaming hot means achieving an internal temperature of 165°F.

But you see where the trouble arises for pâtés and deli meats; we eat them at room temperature which means they never get to a steaming-hot-kill-the-listeria temperature.

How can I reduce my risk of listeria when eating pâté?

Everything we’ve discussed so far is based on food that comes out of manufacturing plants. You can’t control what happens outside of your home so if you’re worried about the risk of listeria from pâté, you can stop buying it from the factory and start making it at home.

Of course, making pâté at home doesn’t guarantee listeria-free pâté, but by practicing food safety at home, you reduce your risk of listeriosis (and other kinds of food poisoning).

FoodSafety.org says the four steps to food safety are:

- Clean – Wash everything often, including your hands, utensils and surfaces.

- Separate – Don’t cross contaminate between foods, especially raw and cooked foods.

- Cook – Food should be cooked to a food-safe temperature.

- Chill – Refrigerate food within two hours or freeze it properly.

There are more details in each of these steps. You can read them all in the Food Safety article, 4 Steps to Food Safety.

What does the National Health Service (NHS) say about pâté and listeria?

The NHS, on their Listeriosis page, puts pâté on its list of problem foods when it comes to listeria. They recommend pregnant ladies avoid “all types of pâté – including vegetable pâté.” Plus, they tell pregnant ladies to stay away from farm animals who are giving birth or have recently given birth, as that’s another source of listeria risk.

What does the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) say about pâté and listeria?

In their article, Get the Facts about Listeria, the US Food and Drug Administration puts refrigerated pâtés on their list of foods associated with listeria contamination.

Interestingly, in their article Listeria from Food Safety for Moms to Be, they say pregnant ladies should not eat “refrigerated pâtés or meat spreads” but that “canned or shelf-stable (able to be stored unrefrigerated on the shelf) pâtés and meat spreads” are okay to eat.

I don’t know how that recommendation jives with listeria-infected production lines, but I leave that for you to ponder on your own.

What does the Government of Canada say about pâté and listeria?

In a specific public health notice about a listeria outbreak related to cooked diced chicken, the Government of Canada says, “High-risk individuals should follow safe food handling practices and should always avoid high-risk food items more prone to contamination with Listeria bacteria such as … ready-to-eat meats such as hot dogs, pâté and deli meats.” (And they listed other foods here too.)

It’s weird I couldn’t find this advice on a more general page but there you have it.

However, on the Government of Canada’s Food safety for pregnant women page, they say much the same as the US FDA. Refrigerated pâtés and meat spreads are on the avoid list for pregnant women. They call “pâtés and meat spreads sold in cans, or that do not have to be refrigerated until they are opened,” the safer choice.

What does the Australian Department of Health say about pâté and listeria?

On their Listeria Fact Sheet, the Australian Department of Health says people with a weakened immune system and pregnant ladies should “try to avoid foods that have a higher risk of L. monocytogenes contamination” which includes refrigerated pâté and meat spreads.

Conclusion

Well, there you have it. Though there haven’t been too many listeria outbreaks associated with pâté, it is possible to get listeria from pâté. The risk of contracting listeria from contaminated food is highest for pregnant women and the effects most detrimental. If you’re not pregnant and you have a robust immune system, listeria poses far less of a threat. May all your pâté be listeria free and delicious!

—

Citations for the studies referenced in this article:

The occurrence of Listeria species in pâté: the Cardiff experience 1989.

Citation: Morris IJ, Ribeiro CD. The occurrence of Listeria species in pâté: the Cardiff experience 1989. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;107(1):111-117. doi:10.1017/s0950268800048731

Link to paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2272023/

Human listeriosis and paté: a possible association.

Citation: McLauchlin J, Hall SM, Velani SK, Gilbert RJ. Human listeriosis and paté: a possible association. BMJ. 1991;303(6805):773-775. doi:10.1136/bmj.303.6805.773

Link to paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1671007/

History and epidemiology of listeriosis

Citation: H. Hof, History and epidemiology of listeriosis, FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology, Volume 35, Issue 3, April 2003, Pages 199–202, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-8244(02)00471-6

Link to paper: https://academic.oup.com/femspd/article/35/3/199/477189

Listeriosis Outbreaks and Associated Food Vehicles, United States, 1998–2008

Citation: Cartwright EJ, Jackson KA, Johnson SD, Graves LM, Silk BJ, Mahon BE. Listeriosis outbreaks and associated food vehicles, United States, 1998-2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(1):1-184. doi:10.3201/eid1901.120393

Link to paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3557980/

Listeriosis outbreak likely due to contaminated liver pâté consumed in a tavern, Austria, December 2018

Citation: Cabal Adriana , Allerberger Franz , Huhulescu Steliana , Kornschober Christian , Springer Burkhard , Schlagenhaufen Claudia , Wassermann-Neuhold Marianne , Fötschl Harald , Pless Peter , Krause Robert , Lennkh Anna , Murer Andrea , Ruppitsch Werner , Pietzka Ariane . Listeriosis outbreak likely due to contaminated liver pâté consumed in a tavern, Austria, December 2018. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(39): pii=1900274. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.39.1900274 [The spaces before commas are part of the citation, not a typo!]

Link to paper: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.39.1900274

Local Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes Serotype 4b Sequence Type 6 Due to Contaminated Meat Pâté

Citation: Althaus, Denise & Jermini, Marco & Giannini, Petra & Martinetti, Gladys & Reinholz, Danuta & Nüesch-Inderbinen, Magdalena & Lehner, Angelika & Stephan, Roger. (2017). Local Outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes Serotype 4b Sequence Type 6 Due to Contaminated Meat Pâté. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 14. 10.1089/fpd.2016.2232.

Listeriosis outbreak associated with the consumption of rillettes in France in 1993

Citation: Goulet V, Rocourt J, Rebiere I, et al. Listeriosis outbreak associated with the consumption of rillettes in France in 1993. J Infect Dis. 1998;177(1):155-160. doi:10.1086/513814

Link to paper: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9419182/

Short-term genome evolution of Listeria monocytogenes in a non-controlled environment

Citation: Orsi RH, Borowsky ML, Lauer P, et al. Short-term genome evolution of Listeria monocytogenes in a non-controlled environment. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:539. Published 2008 Nov 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-539

Link to paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2642827/

Human foodborne listeriosis in England and Wales, 1981 to 2015

Citation: McLauchlin J, Grant KA, Amar CFL. Human foodborne listeriosis in England and Wales, 1981 to 2015. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e54. Published 2020 Feb 19. doi:10.1017/S0950268820000473

Link to paper: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7078583/